Jake & Dinos Chapman Interview

|

The following interview clippings didn't make it into our Jake & Dinos Chapman book, so we have made them available here... NOTE: We have resorted to asterisking some of the words in the text in an attempt to prevent Google blocking this page from its search results. We do not censor any of the text in the book. |

DAVID BARRETT: While the Surrealists would try to make a representation of the subconscious, your works are more like actual expressions of the subconscious - the subconscious drives are made manifest in your sculptures.

JAKE AND DINOS CHAPMAN: On one level, we attempt to have the work make itself, following certain logics. With 'Little Death Machine', for example, that's a really ham-fisted attempt to make a machine that was a representation of the subconscious and the ego and all of these Freudian things. But it went further than that. While of course it wasn't a living thing, to a certain extent it stopped being about something and actually became something. It was like an icon, which is magical. It's a thing in itself: a stand-in for an object, rather than a representation of an object.

We're not interested in making copies of things. When we made 'Hell' we had to become that mad person who would spend two years obsessing over this monstrous vision. So a lot of the work is about stopping it being representational; it goes beyond representation.

Freud is interesting when he doesn't work, when it all goes wrong. The breakdown is the interesting thing.

So 'Mummy and Daddy Chapman' was an attempt to short-circuit Freud?

They can't work. It's a non-starter, truncating the whole genesis thing. 'Mummy and Daddy Chapman' is a sculpture of a situation that can't possibly work; Mummy has both procreative organs and Daddy is just a series of an*ses. It's interesting to set things up that then undermine themselves, that can't sustain a level of investigation.

If two people make work, which part of the artwork is a representation of the ego? The removal of the ego is important to us; neither of us want to be present in the work at all.

Hell (detail), 1999-2000

JAKE AND DINOS CHAPMAN [On their large sculpture, 'Hell']: Because the sculpture took so long to make, it became a repository for all our bad thoughts. Every day we'd come in and try to think of something really awful, and then make it. Like one of those shrines that you throw your little wishes into, but our wishes were not very nice.

DAVID BARRETT: How many figures did it have?

There have been various estimates, from 5,000 to 20,000. There were at least 10,000, but we don't know exactly.

Were the scenes taken from specific references?

Some scenes were based on particular things. One torture device came straight from a book of medieval torture. A lot of things came from medieval macabre drawings. Goya's 'Great Deeds Against the Dead' was in there. The landscapes themselves were invented, though; they weren't based on paintings or anything. The etching that we made of the swastika with a volcano in the middle of it was made while we were working on 'Hell', but before it was actually put together.

When 'Hell' was destroyed in the warehouse fire, everyone who had been critical of our work suddenly turned around and said what a marvellous piece it was, such a shame it's gone, because they thought it wasn't going to come back. That's precisely why we're remaking it - just to get back at those b*stards.

Cyber-Iconic Man (detail), 1996

JAKE AND DINOS CHAPMAN [On 'Cyber-Iconic Man']: It used a badly made pump, a garden pond pump. The fake-blood liquid was slightly viscous so the pump was always working at full capacity and therefore breaking down. Like 'Little Death Machine', 'Cyber-Iconic Man' was another sculpture that didn't behave itself. To this day, if you go to the upstairs room at the ICA in London where it was shown, there's a pink circle on the floor; the dyed water dripped into the collecting bowl and splashed straight back out again.

DAVID BARRETT: You use a lot of different styles in your work, and constantly move between them.

JAKE AND DINOS CHAPMAN: We try to, yes, it's a conscious decision. When an artist ends up with a signature style, you suspect they've stopped thinking and are just fulfilling expectations.

So some of the one-off projects, like 'Studio Tour', are they the result of this tactic?

Partly, yes. We're constantly trying to trip each other up - both physically and mentally.

JAKE AND DINOS CHAPMAN: The good thing about sculptures is that they exist in a funny art-hyperspace that runs alongside the normal, non-art world. There are a lot of very strange things in galleries that you don't apply the usual set of moral rules to. On the whole, people understand this, but then you get agitators - like journalists - deliberately misunderstanding the situation and provoking others to misunderstand it too.

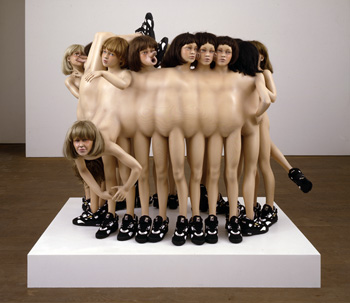

For example, a journalist said to us, 'How can you dare do these things to small girls?' So you think, well, hold on a minute, let's just take that question apart - why is it a girl? So the journalist replies and says, 'Well it's got long hair and freckles'. OK. When Jake was a little child he had long hair and freckles, does that mean that he was a girl then and now, miraculously, he's turned into a man because he's got short hair and his freckles have gone? He says, 'No, no, you know what I mean'. We're like, no, we actually don't know what you mean. You're applying rules to something that they don't actually apply to. This thing is inanimate, it's made from resin and paint. It bears 90% relationship to a mannequin, and maybe less than 10% to things that you can buy in Ann Summers [a chain of s*x-toy shops]. There's no point at which you can say this is a child. It might look like a child from the back, but from the front it doesn't. And then the idea that something with an erect p*nis on its nose could ever be female is also another problem...

The whole point of these objects was actually to back people into a corner with their strange morality. You make an object and put it in a gallery and people don't really see it; they see what they think about things reflected in the object. You might as well put a mirror in the gallery because they're not looking at the object. It's an attempt to force people to take into account their bad thinking. 'Zygotic acceleration...', for example, it doesn't work if you say it's a child or it's children; I've never seen 20 children fused together with adult gen*talia on their faces.

Zygotic acceleration, biogenetic, de-sublimated libidinal model (enlarged x 1000), 1995

DAVID BARRETT: With the full title of that work, 'Zygotic acceleration, biogenetic, de-sublimated libidinal model (enlarged x 1000)', the final part tells you that this is not even a child-sized creature.

Exactly, although people don't read the titles. If you look at our work and think about child abuse, then that would have to be in your mind before you looked at it. You have a matrix of knowledge, of references, before you understand anything, because when you look at something your mind compares it to prior experience in order to understand it. You run through this pattern-recognition process comparing what you're looking at with previous knowledge, and if you don't recognize what you're seeing then you move onto something else that it might be: 'Well, it's obviously not an elephant, maybe it's a pig...' And we do this at such incredible speed that it sometimes goes wrong, so instead of saying 'I don't know what it is', people say 'It is a...', and then make a really stupid analysis of what it is. 'It's an abused child,' they say. Look again; it isn't.

So once viewers make that initial misreading, their ongoing attempts to understand the sculptures simply unravel?

Exactly.

Also, if you're going to talk about abuse, I would say that our objects are more likely to cause abuse than receive it. If you decide that 'F*ck Face' is a child, for example, then it is an unbelievably aggressively empowered one. Its s*xuality is on its face. It's not going to have any problems telling you what it wants.

I've known that work a long time and, for some reason, the idea of child abuse never occurred to me; 'F*ck Face' does not look abused in any way. In fact, as far as I can tell, all the creatures that have an*ses for mouths also have p*nises for noses.

Yes. You can't f*ck them unless you get f*cked yourself at the same time. They're polymorphous s*xual beings and people get very anxious about those grey areas around their morality. They're so desperate to place everything in a comfortable box that, the moment you put something in front of them that doesn't fit in with this, they run around screaming their heads off. Which is the reaction we were trying to provoke; the effect is more interesting than the object. They're like moral hand grenades in galleries. But if you go into a gallery you should be expecting to see things like that. That's what a gallery is: a place where you leave your baggage by the door and you look around and hopefully you see something that makes you think a little bit.

Is shock a part of that?

A shocking incident is something that is totally unexpected and takes you by surprise. A painting in a gallery cannot elicit shock. What you find, though, is that some journalist will say, 'Right, we're going to call this shocking', and all those sheep reading their newspapers will turn around and say, 'It's shocking! I was shocked!'

The problem is that you get journalists who think for their readers and they refer to 'this shocking image'. But if you ask the journalist if they were personally shocked, they say, 'No, I wasn't shocked'. Well why do you say it's a shocking image then? If you're not personally shocked, then it's not a shocking image by your standards. You say you're shocked by 'F*ck Face'? OK, what is it that's so shocking about 'F*ck Face'? Is it the p*nis? If it is, then do you bath in your pants? It's only an object. In fact it's a very poor representation of an object. The middle class love to be shocked; that's how they form their morality, these little shocks, this constant readjustment to the world.

S*x I, 2003

So the shock aspect is down to agitation by journalists?

When the 'Sensation' exhibition was on at the Royal Academy in London everybody was so terribly shocked by everything, like the Myra Hindley painting by Marcus Harvey, for instance - 'this shocking image'. No one mentioned the fact that the photograph the painting was based on was taken from the front page of the Daily Mail newspaper. So you look at your Daily Mail and there's a picture of Myra Hindley on the cover and you go, 'Oh, what an evil lady', and then you turn the page. You're not shocked. There's nothing inherent in that picture that is shocking. What Hindley did, yeah, you can be shocked at that, but not the image; it's just a picture of a slightly scary looking lady. And yet the same people who have seen the photograph in the paper turn up to throw eggs and abuse at a painting of the exact same image.

And then the media portrays this group of artists as if their work is about being shocking.

Exactly, which is not the purpose of the work at all. And then the problem is that people expect it to be shocking, so they come up and say, 'Your work's not as shocking as it could be, what are you going to do about it?' But it's never intended to be shocking in the first place...

JAKE AND DINOS CHAPMAN [On the p*rnographic video artwork, 'Bring Me the Head of Franco Toselli!']: When we first showed the work, the gallerist's parents tried to buy all the copies of the video to destroy them.

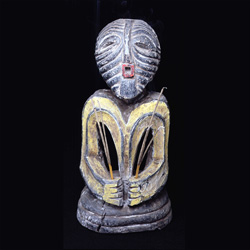

The Chapman Family Collection (detail), 2002

JAKE AND DINOS CHAPMAN [on McDonald's]: The funny thing about McDonald's is that it is considered abhorrent only because the middle classes have decided that the food's not very good, that it's bad for the kids. If the food was good, there wouldn't be a problem. The fact that it's causing massive deforestation and everything else, that would go unnoticed.

DAVID BARRETT: £3 jeans from Asda Wal-Mart are alright, but Happy Meals aren't.

Exactly. It's symbolic of a problem, and the middle class are happy to deal with symbols and not very interested in dealing with actual problems. You march so that everybody sees you march, but the march does nothing.

And the anti-capitalists hurling abuse at McDonald's... there are so many other ways to tackle the issue. Some people have suggested that attacking capitalism is a waste of time; you should really become a capitalist and work to change things from within instead of using aggression, because capitalists can deal with aggression so easily - it's their forte.

DAVID BARRETT: When you've been asked about influences, you've cited the highly systematized American Minimalists, Sol Lewitt and Carl Andre. What is it you like about their work?

JAKE AND DINOS CHAPMAN: They're not very interested in subject matter. They remove all extraneous elements. Aesthetically, their work is not very interesting. And it's not very friendly.

It ticks all the boxes then?

Yeah [laughs]. It's just not very friendly...

Insult to Injury #39, 2003

DAVID BARRETT: You produce a lot of work, almost excessive amounts.

JAKE AND DINOS CHAPMAN: There's nothing worse than not killing something. You don't recognize that something is worth making until you've absolutely ruined it, and then you can turn around and go, 'Yeah, it was alright about two weeks ago' [laughs].

So repetition is an important tactic?

Yes. You don't need to have too many subjects. You can worry away at the same thing for the rest of your life and get no closer to understanding it. Changing subject for the sake of it seems to be a way of avoiding the crunch, which is, 'Why am I doing this? What does it mean? What is culture about? Why do people get interested in it?' That's more interesting than any particular work.

DAVID BARRETT: There is a lot of linguistic play in your work. Some people have said that your work is just a literalization of gutter slang.

JAKE AND DINOS CHAPMAN: Sometimes it is, but that's not all it's doing. It comes back to language. Language separates us from everything else. You couldn't have art without language. Everything gets reduced to language eventually, and the work always exists as language before it becomes sculptures. It's impossible to make something that hasn't already been spoken about, hasn't already been described.

DAVID BARRETT: I remember you once saying that you collaborate because you're only good enough to make one person's work.

JAKE AND DINOS CHAPMAN: We distance ourselves from that now [laughter].

The New Art Up-Close book containing Jake & Dinos Chapman's extended interview can be found here![]()